2020 saw the Libraries meeting student and researcher needs while navigating new safety protocols and being closed for several months early in the year due to the impact of COVID-19. Special Collections continued its work to seek out new additions of rare books and archives vital to understanding the history of Arkansas. Our role in facilitating the “exploration” of Arkansas continues, and we look forward to connecting these resources to our patrons once the division reopens.

One of the most remarkable and important areas of the rare books collection in Special Collections is early printed works on the Mississippi River Valley and the exploration of what eventually became the Territory and State of Arkansas. The University Libraries do a great deal to aid in the university in fulfilling its land grant mission. Books, maps, manuscripts, and photographs about the long, complicated history and diverse culture of Arkansas preserved and made available through Special Collections are one part of fulfilling that mission. Special Collections librarians work each year to identify and make available important or unknown works about the State the university and Libraries serve.

Rare and remarkable printed and manuscript material about Arkansas, or “Arkansiana,” has been collected by the University Libraries since the Arkansas Industrial University was first established in 1871. The first substantial collection of books that would become the seed of Special Collections, not formally established until 1967, was actually the Arkansas book collection former Governor George Donaghey began donating in the 1920s. (Many of them used to be held in a “book cage” in the old Vol Walker Hall library.) Even though the Libraries have spent many decades collecting Arkansiana, the work to preserve and share as complete a picture of Arkansas’ written record as possible goes on.

Here are a few highlights of recent collection development:

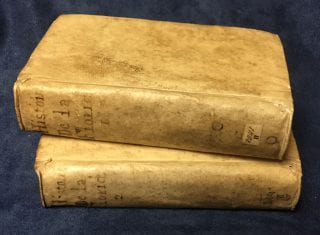

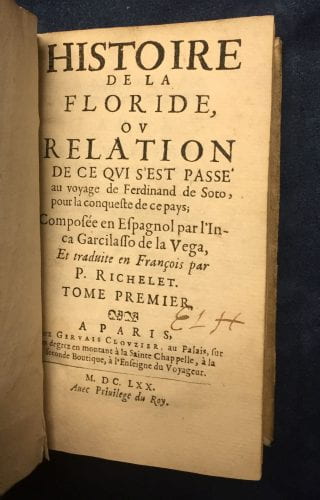

First French Edition of Histoire de la Floride (also known as La Florida del Ynca) by Garcilaso de la Vega.

De la Vega’s history of the earliest Spanish contact in the southeastern United States was first published in Spanish in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1605. A beautifully rebound, pristine example of the 1605 Spanish de la Vega was added to Special Collections in 2012 as the University Libraries’ 2,000,000th book. De la Vega, known as the “The Inca” because of his mestizo heritage as the son of an Incan noblewoman and a Spanish conquistador, was one of the earliest people of American heritage to publish their own writing and was the first historian to publish an account of Hernando de Soto’s landmark and infamous journey, where he and his forces eventually crossed the Mississippi River into what would later be known as Arkansas. (His complete works include the first published histories of Peru, as well.)

The earliest Europeans to establish permanent settlements in Arkansas were not Spanish, of course, but French. It’s possible to imagine that those earliest French explorers may have consulted de la Vega (along with later works by Hennepin or Joutel) to learn more about the indigenous peoples, dangers, and landscapes they would encounter. The first French language edition of de la Vega was published in two volumes in Paris in 1670. Although we have had modern reprintings and the 1605 de la Vega available to students and researchers, we never had a French edition. The example now in Special Collections, small format of two humble volumes in original soft vellum (cow hide) binding are very similar to what our imagined literate explorers would have held.

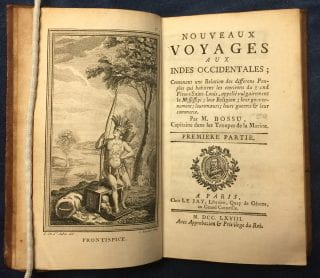

Nouveaux Voyages aux Inde Occidetales by Bossu.

You may wonder how a book titled “Inde Occidetales,” or the East Indies, is Arkansiana. The subtitle is a little more illuminating: Contenenat une Relation des Differens Peuples qui Habitent les Environs du gran Fleuve Saint Louis….It recounts the letters and exploration journals of Jean Bernard Bossu’s first two journeys to the Mississippi River Valley. It is the first of two books published by Bossu, a professional soldier and officer in the French army, about his travels through the European claims in the Mississippi Valley and the native people living in the region, including the Quapaw and the Illinois. Bossu included discussions of their religion, commerce, war practices, and laws. Bossu was influenced by Enlightenment notions of the “noble savage” and became close to the Quapaw of Arkansas.

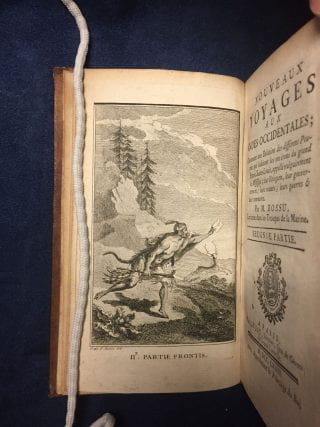

Special Collections already had a copy of Bossu’s other important work, Nouveaux Voyages dans l’Amerique Septentrionale which recounts his third trip to the region. Published in 1777, the second book tells of Bossu’s exploration during the period of Spanish rule in the Louisiana territory. Both books by Bossu include important romanticized illustrations of the “noble savages” Bossu reported about to Europeans. Although the text is usable in the copy of the 1777 book, and includes a remarkable early illustration of the Quapaw hunting, it is not in great condition. Stable enough for students to access (and to have been include in the recent Arkansas Territory exhibit), it had been poorly rebound, the leaves were damaged in places, and it does not showcase some of the characteristics of an 18th century book that so effectively transport students to the time and place a historic text was created and first used.

The newly added copies of Bossu’s first book are in 18th “sprinkled calf” leather binding and include four different engraved illustrations showing important interpretations of the indigenous people encountered, and brutally treated and unjustly displaced, by European and American imperial expansion, even as the Arkansas Post and what became our State were being established. Special Collections already had an early English translation of Bossu’s first work.

Bradbury’s Travels in the Interior of America in the Years 1809, 1810, 1811.

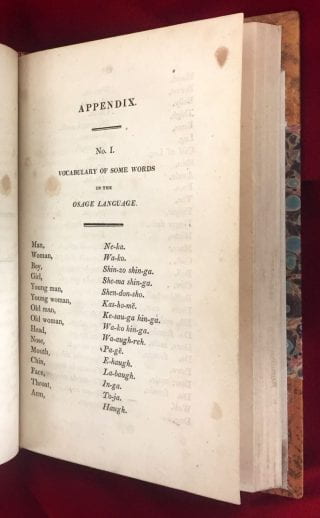

Although other explorations of the Louisiana Purchase territory and the land that would become Arkansas are better known today, the 1817 publication by Englishman John Bradbury adds even more detail to our understanding of how the region was studied and incorporated into the rapidly growing young United States. Special Collections holds first editions of nearly all of the earliest published accounts of Arkansas published in the early republic period, although Bradbury had not been in the Libraries until now. With this acquisition, we get observations from even before the Arkansas territory came to be created. These include transcriptions of Osage language, plus the natural observations taken alongside Thomas Nuttall on the journey they shared with the Astor expedition of 1811 all the way to Oregon.

Although other explorations of the Louisiana Purchase territory and the land that would become Arkansas are better known today, the 1817 publication by Englishman John Bradbury adds even more detail to our understanding of how the region was studied and incorporated into the rapidly growing young United States. Special Collections holds first editions of nearly all of the earliest published accounts of Arkansas published in the early republic period, although Bradbury had not been in the Libraries until now. With this acquisition, we get observations from even before the Arkansas territory came to be created. These include transcriptions of Osage language, plus the natural observations taken alongside Thomas Nuttall on the journey they shared with the Astor expedition of 1811 all the way to Oregon.

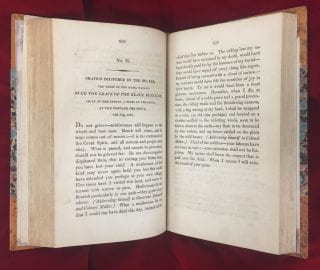

Among recountings of interactions with the Osage and other First Nations of the Missouri Territory, and observations of plants and minerals, this copy of Bradbury’s Travels includes older bookseller notations and the original errata slip (the publisher’s insert, added after printing, indicating the known mistakes in that edition, evidence of the volume’s rarity and position in the history of printing). Bradbury includes a transcribed oration of Big Elk and a glossary of the Osage language, gathered when they still lived in the Arkansas area before the Territory was established in 1819.

The published accounts of the famed Lewis and Clark expedition are familiar to most Americans, as in passing as a detail in a history class. The other Jeffersonian expedition through southern Arkansas by Dunbar and Hunter was included by Andrew Milson in his interesting recent book from the University of Arkansas Press, Arkansas Traveler’s: Geographies of Exploration and Perception, 1804—1834.

Milson uses the writings of four important naturalists – William Dunbar, Thomas Nuttall, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, and George William Featherstonhaugh – to describe the evolving understanding of the people and landscape of Arkansas. Similar to the other rare books described above, the Libraries made efforts to make the text of Bradbury available through modern reissues and microfilm. Now, students, professional researchers, and any interested member of the public can hold and experience the real book as it would have appeared in 1817 as they continue their own explorations of Arkansas.