This blog post was provided by Craig Huddleston, a recent graduate of the University of Arkansas history department. Huddleston has been conducting research in the University Libraries through an internship with Special Collections.

In the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, African Americans were forced from their homelands, put under bondage, and built a nation with their own blood, sweat, and tears. Then, after a four-year-long, bloody and grueling civil war between the Northern United States of America and the Southern Confederate States of America, several new amendments were added to the United States Constitution. These new amendments were the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. These amendments ended slavery, gave African Americans citizenship, and established universal male suffrage across the country. In the immediate years that would follow the ratification of these amendments, African Americans would experience that birth of rights that they had never seen before, but these rights would lead to unforeseen consequences for African Americans, particularly in the Southern States.

This blog will look at African American legislators who served in the Arkansas General Assembly during the Era of Reconstruction. This blog entry will look at specific legislators and what the legislation that these State Representatives and State Senators were able to pass. This blog entry will also try to show that, because of what they brought to the table and were able to help pass into law, that these legislators might have been the most important group for the state of Arkansas during the period of Reconstruction.

In the years after the American Civil War, the nation began to let Confederate States back into the Union, but on several conditions. The former Confederate States would be required to write new state constitutions. The states would have to adopt the newly aforementioned 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. They were also told not to publicly adhere to the mythology that was the “Lost Cause” of the former Confederacy. Unfortunately, these state governments did not follow either.

Because of these two realities, by 1867, President Johnson ordered that all former Confederate States must go through “reconstruction” in the hopes that they would try and shed the past of the confederacy and allow African Americans to be able to fully use the rights that had been given to them in the past few years. The three major groups that would be involved in Reconstruction-era politics in Arkansas were Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and African Americans.

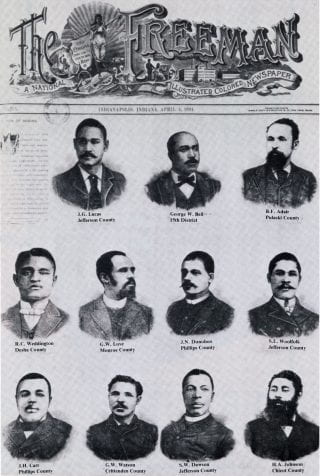

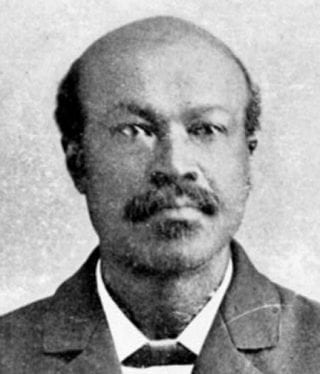

Shortly after President Johnson ordered Reconstruction, Arkansas held elections. In these elections, Arkansas elected a Republican majority in their government for the first time. African Americans were also elected various governmental positions for the first time in state history as well. In “African American Legislators in the Arkansas General Assembly, 1868-1893 by Dr. Blake Wintory, we see that seven freedmen were elected. Six men went to State House and one man went to the State Senate. From 1868 to 1874, thirty-two men would be elected to the General Assembly. Most of these men that were elected to the General Assembly were from counties in the Delta Region. Some of these men would include William H. Grey, Richard Dawson, Ferdinand Davis, James T. White, Anderson L. Rush, A.M. Johnson, and James Mason.

When the new Republican-controlled General Assembly session started, there was a lot of sweeping legislation that would pass during this time. Much of this legislation was vastly different and much more radical than what the state of Arkansas had ever seen before. Much of the legislation was passed through and agreed on pretty easily. One of the major platforms of the Republican Party of Arkansas that they would pass into law quickly was economic expansion through building new railroads. During the period of Reconstruction, around of 662 miles of railroads would be built. They also appropriated the funds that were needed to fund public education throughout the state. During this time, a college, the Arkansas Industrial School, would be established in Fayetteville. This college would later become the University of Arkansas. In an academic essay titled, “The Africans Have Taken Over Arkansas”: Political Activities of African Americans in the Reconstruction Legislature, Chris W. Branam argued that there was a source of disagreement on education, and that was whether to allow segregation in public schools. One of the prominent African American legislators that was in support of allowing segregation in schools, and that was State Senator James Mason. Mason was also the son of the wealthy Fayetteville planter Elisha Worthington.

While there was much opposition to this, Governor Powell Clayton ultimately allowed segregation in public schools. According to Branam, there was one defining bill that caused a true split, and this was Senate Bill 11. This bill would bring regulation to roads to highways. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate, but would be a different story in the House. The bill only passed by a vote of 35-27. Representatives Grey and White were harshly against the bill, while Representative Rush supported it. Grey and White never stated on record for why they voted against the bill, but in Branam believes that they voted against it the bill because it was “discrimination against poor people, including African Americans.” It is believed by Branam that this was due to a provision that was put in place that would allow men in the state to not have to work on building new roads if they “paid two dollars a day in lieu of such labor.”

During these few years of Reconstruction, the brief period when African Americans would have freedoms that they had never seen before, such as voting and holding public office. Unfortunately, these rights would soon be taken when the Old Guard of Arkansas would get back into power, and undo much of the progress that had been made from the years of 1868-1874. African Americans would not see many of these rights restored until after the modern civil rights movement of the mid-20th century. In the next blog, the reason why Reconstruction ended in Arkansas will be discussed. Also, what happened to African Americans from the end of Reconstruction to the start of state-sponsored Jim Crow in Arkansas will be looked at in further detail as well.

For further reading, see:

Branam, Chris W. “”The Africans Have Taken Arkansas”: Political Activities of African Americans in the Reconstruction Legislature.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73, no. 3 (2014): 233-67. Accessed April 29, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/24477452.

Wintory, Blake J. “African-American Legislators in the Arkansas General Assembly, 1868-1893.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly65, no. 4 (2006): 385-434. Accessed April 29, 2020. doi:10.2307/40028092.

DeBlack, Thomas A. “Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861-1874, the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/civil-war-through-reconstruction-1861-through-1874-388/.