This is the second blog written by Craig Huddleston, a University of Arkansas history graduate and Spring 2020 Special Collections intern. Huddleston’s blogs resulted from research he conducted using Special Collections resources. For more information on becoming an intern, visit the Get Involved page on the Special Collections website.

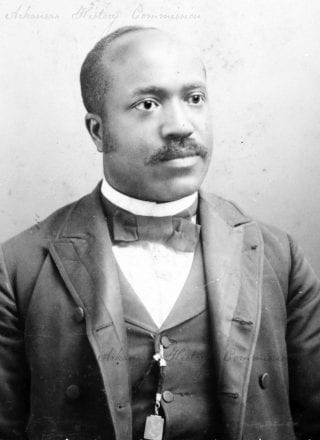

A previous blog post discussed the role of African American legislators in the Arkansas General Assembly during the period of Reconstruction. More specifically, it investigated what led to “Radical Reconstruction” happening across the former Confederacy, which lasted in Arkansas from 1868-1874, and the legislators and prominent legislation they were able to pass. The end of the entry alluded to the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas. This post will discuss why Reconstruction ended in Arkansas, along with the new “Redemption” government of Arkansas, from its inception in 1874 to the very first years of the 20th century when Arkansas had fallen under state-sponsored Jim Crow.

The Republican-controlled Reconstruction government of Arkansas brought a lot of economic and education expansion. However, the state also accrued a large amount of debt during the years of Radical Reconstruction. While Arkansas had a history of debt trouble since its earliest years in the 1830s, the debt skyrocketed during Reconstruction. This caused many Arkansans to become enraged with the Powell Clayton-controlled government. There were also widespread accusations of large-scale corruption in the Clayton administration. Many of the Arkansans that were upset were conservative Democrats who had opposed this government from the beginning of Reconstruction. The vast majority of these conservative Democrats were men who had lost their voting rights after the Civil War because of their allegiance to the Confederacy.

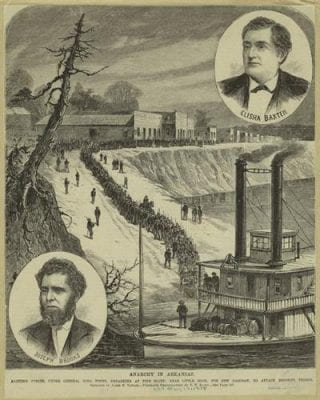

The conservative Democrats were not the only group upset with the Clayton regime. In fact, members of his own Republican Party were upset with Clayton. These Republicans were a part of the liberal Republican faction. They were upset about alleged corruption with Clayton and his allies, while also being openly critical of Clayton for being too moderate on economic expansion and civil rights for African Americans. In Brindletails, Minstrels, Hercules, and Lady Baxter: The Brooks-Baxter War and the End of Reconstruction in Arkansas Thomas DeBlack writes that there were two leading members of the liberal Republicans: Lieutenant Governor James Johnson and Joseph Brooks.

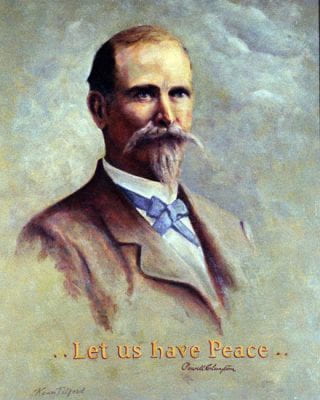

Due to these realities, Governor Clayton felt pressured from both sides of the political aisle, and he began to fear that he would lose his bid for reelection in 1872. Clayton decided to run for appointment to the United States Senate. Two prominent figures quickly rose from the Republican Party as the hopefuls to become Governor of Arkansas: the aforementioned Joseph Brooks and Clayton ally Elisha Baxter. The election was held November 5, 1872. The results came back with Elisha Baxter winning. Immediately, supporters of Joseph Brooks cried foul play. They believed that there had been widespread voter fraud in favor of Baxter. While this might have been true, and voter fraud would be an issue for Arkansas elections until after the mid-20th century, Elisha Baxter was nevertheless sworn in as governor. As governor, Baxter ended voting restrictions on former Confederates and allowed a vote for the state to hold a new constitutional convention. These two acts created the demise of the Reconstruction government in Arkansas.

While all of this was going on, Joseph Brooks had petitioned through the courts that the election of 1872 was fraudulent. The courts agreed, and Brooks became the new governor. Supporters of both men rounded up weapons and met up in Little Rock, and conflict ensued. Although short-lived, this would become known as the Brooks-Baxter War, and it marked the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas. Voters in 1874 allowed a new constitutional convention and Democrat Augustus Garland was elected governor in November of 1874.

With Reconstruction over in Arkansas, the role of African Americans would change in politics, but not for quite a few years. In the 1870s and 1880s, governors such as Augustus Garland advocated for keeping voting rights and other civil rights for African Americans. African Americans continued to hold elected office, serving in both state and local positions. During the next few years, Democrats would begin to divide. According to Redeeming Arkansas: The Constitution of 1874 and Post-War Politics by Rodney Harris, there were two groups, the “New Departure” and “Straight-Out.” The New Departure Democrats were Democrats like Augustus Garland who supported civil rights to a degree and wanted to move on from the Civil War. The Straight-Out Democrats were very outspoken supporters of the mythology of the “Lost Cause” and they were not in favor of any kind of civil rights.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, The New Departure Democrats ran government in the state. By the early 1890s, the Straight-Out Democrats rose to power and started passing Jim Crow laws, such as segregation, and laws to help disenfranchise African Americans. After the early 1890s, the Arkansas General Assembly did not have an African American official until after the modern Civil Rights movement.

By this point, the Democratic Party of Arkansas had publicly become the party of white supremacy. They replaced the picture of George Washington that hung in hall of the House of Representatives in the state capitol with a picture of Jefferson Davis and elected the staunch segregationist and openly racist Jeff Davis governor at the turn of the 20th century. During these next few decades, many African Americans would leave the state in the hopes of better lives in Northern states, but for the ones that would stay, they would have to face the turmoil that was the Jim Crow South.

For further reading, see:

Brindletails, Minstrels, Hercules, and Lady Baxter: The Brooks-Baxter War and the End of Reconstruction in Arkansas by Thomas DeBlack

Redeeming Arkansas: The Constitution of 1874 and Post-War Politics by Rodney Harris

The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880-1920 (Dissertation) by Fon Louise Gordon