[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″ inner_width=”auto” inner_max_width=”982px”][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ custom_padding__hover=”|||” custom_padding=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.0.3″ text_line_height=”1.4em” text_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”text_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ text_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” text_text_shadow_vertical_length=”text_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ text_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” text_text_shadow_blur_strength=”text_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ text_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” link_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”link_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ link_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” link_text_shadow_vertical_length=”link_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ link_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” link_text_shadow_blur_strength=”link_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ link_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” ul_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”ul_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ul_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” ul_text_shadow_vertical_length=”ul_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ul_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” ul_text_shadow_blur_strength=”ul_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ul_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” ol_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”ol_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ol_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” ol_text_shadow_vertical_length=”ol_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ol_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” ol_text_shadow_blur_strength=”ol_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ ol_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” quote_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”quote_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ quote_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” quote_text_shadow_vertical_length=”quote_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ quote_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” quote_text_shadow_blur_strength=”quote_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ quote_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_2_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_2_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_2_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_2_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_2_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_2_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_2_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_2_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_2_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_3_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_3_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_3_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_3_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_3_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_3_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_3_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_3_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_3_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_4_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_4_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_4_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_4_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_4_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_4_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_4_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_4_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_4_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_5_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_5_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_5_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_5_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_5_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_5_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_5_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_5_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_5_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” header_6_text_shadow_horizontal_length=”header_6_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_6_text_shadow_horizontal_length_tablet=”0px” header_6_text_shadow_vertical_length=”header_6_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_6_text_shadow_vertical_length_tablet=”0px” header_6_text_shadow_blur_strength=”header_6_text_shadow_style,%91object Object%93″ header_6_text_shadow_blur_strength_tablet=”1px” box_shadow_horizontal_tablet=”0px” box_shadow_vertical_tablet=”0px” box_shadow_blur_tablet=”40px” box_shadow_spread_tablet=”0px” z_index_tablet=”500″]

For a few hours on Saturday afternoon, December 6, 1969, the eyes of America were trained on Fayetteville, Arkansas. That Saturday the University of Arkansas hosted a marquee match-up between the top two football teams in the nation with the University of Texas visiting. 1969 was a pivotal year for the campus culture at the University of Arkansas, and the “Game of the Century” as the game was called,was the culmination of a transformative semester in Fayetteville that saw protests by African American students demanding greater representation and less racism on campus, as well as students opposing the Vietnam War. The days leading up the game raucous partying and racial violence colored the nation’s view of the Fayetteville. Part two of a look at the 1969 at the University of Arkansas fifty years later draws on student publications such as the Razorback yearbooks and Traveler newspaper and other historical sources to explore the year that brought Muhammad Ali and President Nixon to Fayetteville and saw “Dixie” lose its hold.

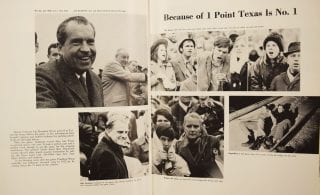

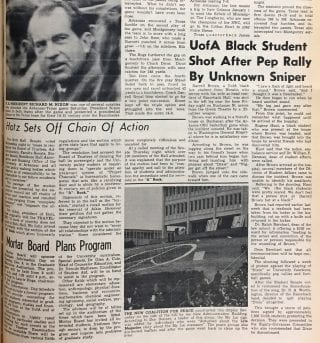

A focus of the cultural divide in the United States in 1969 was the nation’s elected leader himself. Reviled by the anti-war left and the counterculture, President Richard M. Nixon was also noted football enthusiast. He arrived via helicopter in Fayetteville to attend the game. A photograph of Nixon and other notable political figures sitting in the stands is preserved in Special Collections and is available as part of the Libraries digital collections.

Those sitting with the president include Governor Winthrop Rockefeller, Congressman John Paul Hammerschmidt (far left), University President David Mullins (lower center), future President George H.W. Bush (right looking at the camera,) and Senator J. William Fulbright to the left of Bush. President Nixon and the other political dignitaries joined more than 40,000 rabid Razorbacks fans. Billy Graham, the most famous religious figure in the United States, attended with his son as special guests of President Nixon’s.

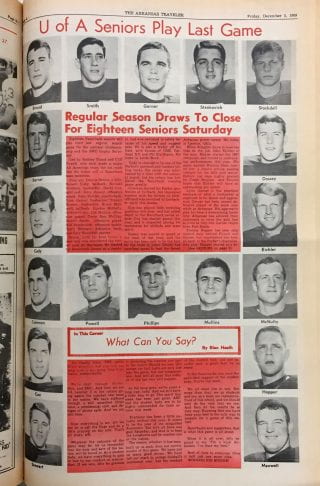

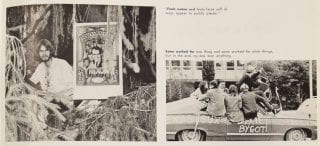

In his 2002 book longtime journalist and sportswriter Terry Frei named the legendary football game “Dixie’s Last Stand.” In addition to the newsworthy folks in attendance, the game was the last one between Arkansas and Texas—and any collegiate football game with national significance—with only white players on the field. The unusual December regular season game pitched two of the leading programs and bitter Southwest Conference rivals against each other. Although dominated for decades by Texas, the storied rivalry that began in 1893 had become in the 1960s a deciding game for both the SWA and national championships. Texas was the 1963 national champion being followed by their conference foe the very next year. Since even before the 1964 National Championship team, Arkansas’s coach Frank Broyles was regarded as one of the greatest football minds in the country, producing professional players and a generation of future coaches. 1969’s star-studded affair included numerous All-Americans and future pros for both Arkansas and Texas. Arkansas included one African American player in its official program. According to Frei’s research, Hiram McBeth III, a marginally talented walk-on who had integrated the team, nominally at least, as part of a campus wide integration effort orchestrated by the Black Americans for Democracy was on the Razorbacks B squad. The first scholarship player ever recruited by the Razorbacks was Jon Richardson, who wouldn’t be on the team officially until the following year. Arkansas and Texas had both gone after Richardson, an outstanding running back and student-athlete from Horace Mann High in Little Rock. SSOC, or the Southern Student Organizing Committee, was also active in Fayetteville in 1969. Alternative press author and environmental activist Joe Neal served as secretary of the local chapter of SSOC as a student at the UofA. Recognized over objections by the Student Senate in 1968, SSOC had started as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. In Fayetteville SSOC led efforts to protests Napalm and the connection between the UofA and corporations such as Dow Chemical considered by Anti-War protesters as part of the “military industrial complex.” SSOC also supported students trying to avoid the draft. Yet another sit-in by an anti-war protester was staged in the cypress tree in front of Student Union in Memorial Hall before Nixon arrived on campus. Neal recounted the student anti-war activism and tree protests in a 1984 article in the Grapevine independent newspaper.

Earlier in 1969, Dr. Gordon Morgan became the first African American faculty member hired by the University when he was appointed Associate professor of sociology. Born in Faulkner County, Arkansas in 1931, Morgan earned a M.A. from the University Arkansas in 1956 and a Ph.D. from Washington State in 1961 before traveling the world as an educator and researcher and returning to teach in his home state. Morgan recounted the experience of integration and the conditions confronted by African American students, staff, and faculty, including the pivotal events of 1969, in his book, The Edge of Campus. Interviews with Morgan are available from the Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History.

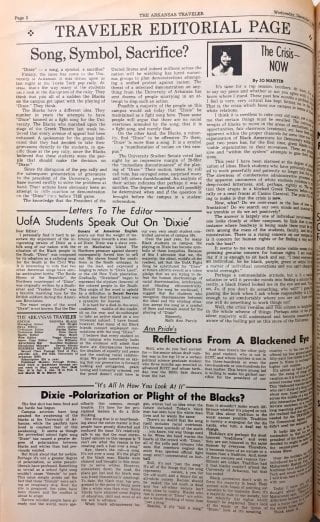

The 1970 edition of the Razorback yearbook, covering the events of fall 1969, recorded that “Black Students Force ‘Dixie’ issues.” African American students were able to prevent “Dixie” from being played by the band at two pep rallies in November, and the campus held a moratorium on racism November 7th. Fall of 1969 saw the initial “Black Studies Program” on campus after years of advocacy by black students. With their more vocal presence on campus, Black students felt a near constant threat of violence in the days leading up to the game. As Gordon Morgan described, partying and disruption increased throughout the week, with some white student driving through campus honking horns, yelling, and flying Confederate flags. “Keggers” during the day and all-night parties were part of an escalating and increasingly out of control atmosphere on campus as some white students used the opportunity to express racial anger and some scores of students abandoned attending classes altogether. This followed months of protests by Black students against the playing of the song “Dixie” by the marching band and display of Confederate flags at the games.

December 2, a few days before the Texas game, and after news that President Nixon was attending, the Student Senate voted unanimously to recommend stop playing “Dixie” at the football games. For weeks hundreds of students attended Senate meetings, students delivered multiple petitions to President Mullins, and letters to the editor and public debates about the issue raged including in print in the pages of Traveler. At the November 30th Pep Rally, black students had marched to the Chi Omega Theater to disrupt the event and prevent the playing of Dixie. These events came after months of increasing protests and formation of the Black American for Democracy student activism group. As white Senators pointed out, and Black activists acknowledged, if the decision was left to the popular will of the students then “Dixie” would continue even as many white students expressed support for the efforts of their African American classmates to keep Confederate paraphernalia and “Dixie” out of student events.

Razorback Band Director Dr. Richard A. Worthington acquiesced to student protests by ending the playing of “Dixie” entirely following a vote by the student Senate recommending it being discontinued. Counter petitions signed by more than a thousand students tried to keep the song part of sports celebrations. As the game approached, the UA campus and national media anticipated a monumental event. The Friday, December 5th Traveler includes an article about the ABC television network expecting 60 million viewers. Alongside that article and others about the national attention focused on Fayetteville was an announcement from the Deep End café, located in the Presbyterian Church. Poet Allen Ginsberg had stopped into the spot to hear local poets during his visit to campus earlier that year in May. The Deep End was hosting “A Black-White Dialogue” open mic the night before the game the next day, the last of numerous efforts across campus to promote greater racial understanding diffuse possible violence.

Unfortunately, those efforts for racial reconciliation were unsuccessful, at least in the short term. At the Pep Rally Friday students waved large Confederate flags and carried signs with racist messages. A photo that ran in the northwest Arkansas Times, included by J. Neal Blanton in his elegiac book recounting of “The Game” and Texas’ victory shows students brandishing signs and flags and other racist messages. Indeed violence did result later that night after the Pep Rally and a basketball against Oklahoma State. Darrell Brown from Horatio was shot in the left leg by unnamed assailants in a car as he jogged home after the basketball game. They shouted Dixie and racist epithets at him as they shot. The Arkansas Alumnus offered later in the month that the shooting took place on Buchanan Street across the street from the Greek Theater. Black students had to be escorted to the stadium the next day, and white students yelled racial slurs and hurled bottles and other objects at them, threatening more violence with flag poles and other objects that were not supposed to be in the stadium, even as ABC interviewed Nixon at halftime about the game and he correctly predicted that Texas would outlast the Hogs. After the loss, anger continued to spill out onto the streets of Fayetteville and across campus. After continued harassment, African American students gathered together at a rental house on Buchanan seeking safety in a larger group and some armed themselves in case they were attacked. The Monday, December 8th Traveler lead with the story, appropriately of the Razorbacks devastating one point loss. To the right of the picture of Nixon in the stands “UofA Black Student Shot After Pep Rally By Unknown Sniper.” Monday after Arkansas lost to Texas 15-14, the Traveler reported about racial violence before the game, “UofA Black Student Shot After Pep Rally By Unknown Sniper.” A photograph next to article also reported on the giant peace sign installed by the “New Coalition for Peace” on the hill by the new Administration Building, overlooking the field.

Brown was a first-year law student in 1969, after having graduated as an undergraduate in the Spring. The Dean of the Law school offered $100 for information on the people that shot Brown and fundraising by faculty and staff added $1500 more. Unmentioned in news accounts following the racist attack Brown suffered is that he was perhaps the first African American football player to integrate the Razorbacks. As a freshman Brown was a walk-on running back. Terry Frei interviewed Brown about his experience as a young player in Arkansas for “Dixie’s Last Stand.” Brown practiced as a member of the freshman team and saw limited playing time. Following injuries practicing before trying to join the varsity Brown left the Razorbacks with official playing time. Gordon Morgan, a student on campus during the 1960s and an early African American faculty member beginning in 1970, discussed the pivotal moments of race relations in the late 1960s in his history The Edge of Campus. Brown was the first recipient of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Award established to honor the civil rights leader’s legacy. Brown had received a $1200 Carnegie Law Grant from the Hubert Lehman Education Fund before the shooting. He and his wife also served as head residents at Razorback Hall. That same issue of the Traveler that reported Brown’s shooting and Arkansas’s loss to Texas, also noted the historical moment the University was witnessing. Photos and reprints of historical letters looked back to Razorback stadium in the 1920s and 1930s. In some ways such as seen through the football program, 1969 marked a highwater mark for the University of Arkansas. It was after that pivotal year, however, that the campus became more fully integrated with opportunities available for African Americans at all levels, from undergraduate studies to Professorships. As the University continues to expand and achieve ever greater success as a research institution, the five decades since the “Game of the Century” has seen the positive influence of the University only grow.

Further Reading:

Neal Blanton, Game of the Century: Texas vs Arkansas, December 1, 1969 (1970).

Evin Demirel, African American Athletes in Arkansas: Muhammad Ali’s Tour, Black Razorbacks, and Other Forgotten Stories (2017).

Terry Frei, Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming: Texas v. Arkansas in Dixie’s Last Stand (2002).

Gordon D. Morgan and Izola Preston, The Edge of Campus: a Journal of the Black Experience at the University of Arkansas (1990).

The University of Arkansas Yearbooks: https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Razorbacks.

The Arkansas Traveler newspapers: https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Traveler.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]