Have you ever visited a museum, library, or archive, and wondered how they create their exhibitions? How do staff members decide what topic to explore? How are items selected? Who writes the text? And how can I get involved?

Well wonder no more! Here at University Libraries, the Special Collections Department has a vibrant exhibitions program that is driven by a cross-departmental team of library faculty and staff. The purpose of our exhibitions program is to support the research, teaching, and learning at the University. These displays are a way for the community to learn about our collections, and we hope that experience encourages them to use the collections to explore an interest or to do further research.

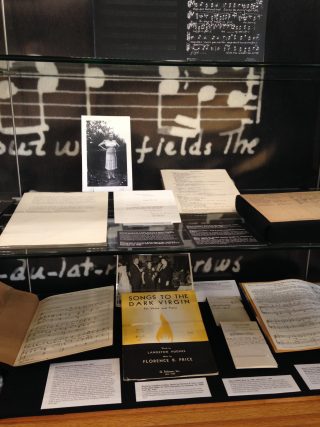

In February, I co-curated the exhibition, “Rediscovering Florence Price: The Life and Work of the Composer” with our Outreach and Research Services Librarian, Joshua Youngblood. The planning for any successful exhibit begins months, and often years in advance. Our team has an exhibition’s calendar that maps out our program for about 18 months at a time. Using a calendar approach, enables us to consider what if any anniversaries are coming up in the year that we’d like to connect our display with, what classes are faculty teaching that might connect with our collections, and what collections do we feel should be highlighted to increase their use. The Florence Price Papers is the second most heavily used collection in our department’s holdings. Accessed over 70 times in 2017, this significant composer continues to attract scholarly attention worldwide.

In February, I co-curated the exhibition, “Rediscovering Florence Price: The Life and Work of the Composer” with our Outreach and Research Services Librarian, Joshua Youngblood. The planning for any successful exhibit begins months, and often years in advance. Our team has an exhibition’s calendar that maps out our program for about 18 months at a time. Using a calendar approach, enables us to consider what if any anniversaries are coming up in the year that we’d like to connect our display with, what classes are faculty teaching that might connect with our collections, and what collections do we feel should be highlighted to increase their use. The Florence Price Papers is the second most heavily used collection in our department’s holdings. Accessed over 70 times in 2017, this significant composer continues to attract scholarly attention worldwide.

As Joshua and I set out to curate this exhibition, we considered a few key questions, which commonly serve as a jumping off point for this kind of work:

- What kind of story do we want to tell through this exhibition?

- What specific items will help us tell that story?

- Who are the experts who could contribute to our display?

- Who is the audience for the exhibition?

We decided to tell a story that documents Price’s training and development as a musician growing up in Arkansas in the early 1900s. That narrative enabled us to explore her schooling and musical training, her family life, and her impact as a composer. Presented in the cases chronologically, the narrative is easy to follow.

With the story decided, picking items came next. Because we work with one of a kind or unique materials, when curating an exhibit it’s important to consider the preservation needs of each item. We also consider the impact an exhibit will have on our researchers, since an exhibit like this one will be on display for a number of months. We work with the Research Services team in the department to scan high-use items, to ensure that the intellectual content is available to potential researchers, even if the original object is on display.

When picking items, we think about which ones provide the best evidence for the story we’re trying to tell. Additional considerations include, how easy is the item to see or read? How much explanation will we need to provide for a viewer to understand the item’s significance? Do we have the space in the display cases to fit the item? Is there enough color variance between items, or will the display look too bland because we’ve picked all letters on cream paper?

The next step is to consider which experts might be interested in partnering with us to write the exhibit text. For this exhibit, we’re grateful to work with two former faculty members, Drs. Jim Greeson and Barbara Garvey Jackson. They wrote about Price’s career and her legacy. Joshua and I focused on writing the labels explaining what each item is, and its importance to our story. Our audience for an exhibition on the 2nd floor of the library is students and the public. Since our department is located on the 1st floor of the building, we don’t have the same opportunity to answer questions viewers may have, as we do when we curate exhibits for spaces within our department. We try to keep this text straightforward and short, to encourage people to take the time to read it!

As we continue to pick items to include, we also pay attention to which items might be signature pieces. These are the kinds of items that we might want to reproduce and make bigger to draw the viewer’s attention to them and their significance. Or these items may have been considered incredibly important to the person, event, or group we’re showcasing.

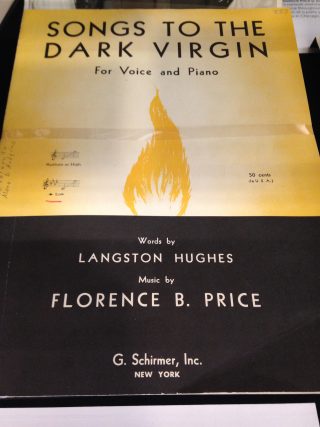

In the Florence Price exhibit, one of the signature items is a musical score, Songs to the Dark Virgin: for voice and piano. This piece is one of my favorites because it’s a collaboration between two great artists: Florence Price and poet, Langston Hughes. Hughes wrote the words, and Price wrote the music for this piece published in 1941. This musical score is a great example of two artists working together to create something beautiful.

The next step is to work with the Preservation librarian, Mary Leverance, to be sure that the items we’ve picked can be displayed for several months. As she looks at each item, Mary considers the impact light, temperature fluctuation, and humidity will have on each object. She also makes suggestions about how best to display items to help ensure there’s no damage done to them while being on view. For example, if we want to include a book, she suggests how to open the book so the book’s binding or pages don’t become damaged over time.

The next step is to work with the Preservation librarian, Mary Leverance, to be sure that the items we’ve picked can be displayed for several months. As she looks at each item, Mary considers the impact light, temperature fluctuation, and humidity will have on each object. She also makes suggestions about how best to display items to help ensure there’s no damage done to them while being on view. For example, if we want to include a book, she suggests how to open the book so the book’s binding or pages don’t become damaged over time.

The next step is installing the items and the item labels in the display cases. Cat Wallack, the Architectural Records Archivist, designed the exhibit signs, and created the supports to best display each item. This work requires tremendous attention to detail and precision to ensure that no object will be damaged while on view.

What only takes a thousand words to describe, takes months of planning and work in real time. Our exhibitions program is a critical part of our outreach efforts, and we’re delighted to share these collections with you.

I encourage you to visit the Mullins Library and see not only the exhibit on Florence Price on view through summer 2018, and our other displays as well.