Hello! This is the first entry from the Special Collections of the University of Arkansas Libraries on 365 McIlroy. We’ll be adding updates about ongoing projects and showcasing all of the many different types of work going on in Special Collections. Here you’ll find information on new collections being processed, digital collections that allow people to access our collections from anywhere, and upcoming events, as well as have opportunities to take a deeper look at our exhibits, outreach efforts, and the scholarship of our staff and researchers.

Folksongs Inside and Outside of Special Collections

August 28, 2015, the University Libraries officially opened the Ozark Folksong Collection digital collection. The collection lets anyone listen to more than 4600 recordings (and view transcriptions with detailed descriptions!) representing the largest collection of Ozark folksongs anywhere. It took years of hard work by librarians and archivists such as Lora Lennertz, Director of Access and Research Services, to bring the decades of work by folklorist Mary Celestia Parler and her students to the broader public through this amazing digital resource.

One of the many interesting historical connections related to folk music in Arkansas is that between Cooperative Extension Services, headquartered for the state of Arkansas at the University, and early folk revival efforts. In the recently mounted physical exhibit in Special Collections, “A Tune Caused the Valley to Ring,” two images and an album provide interesting evidence illustrating that connection.

The first image is from page 189 of A History of the Agricultural Extension Service in Arkansas by Mena Hogan, a thesis completed in 1940 for a Master’s of Science in Agricultural Education for the University of Wisconsin.

Hogan’s original caption reads: “The development of leadership in recreation, the raising of standards of rural entertainment, and home talent development have been major objectives in the community activities program for Arkansas Farm Families. The above group of 4-H players dancing on the grass at the University of Arkansas campus illustrates the types of recreation being taught throughout the state.” Along with the dancers in front of Old Main, under the trees of the University of Arkansas Arboretum, other 4-H students play guitars and fiddle.

More than 70 years since Hogan wrote her thesis, it remains one of the best sources of information on the history of Arkansas’s early Cooperative Extension Service. It includes several other notable images, pasted as prints into the original bound copy. Other images include an African American extension agent giving an instruction session, early canning training, New Deal Era “plowing up” of planted crops, and images of new developments in agricultural production such as the use of freezers for long term food preservation.

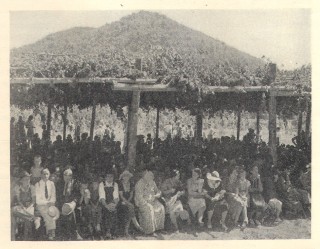

The second image illustrating the connection between Cooperative Extension Services and the folk revival is actually taken from a World War II era newsletter. That image shows a large crowd under a specially constructed brush arbor attending the very first Stone County Folk Festival, 1941. It was included in the article “Rural Arkansas Revives its Folk Music,” by June Donahue, which appeared in the Recreation magazine published by the National Recreation Association, February 1942, page 669. Approximately 3,000 people attended the festival, one of every several being held in Arkansas counties at the time that grew out of work by the Cooperative Extension Services Home Demonstration Clubs and 4-H groups. (To find out more about Arkansas’s Cooperative Extension Services, we also have the historical records.)

The Cooperative Extension Services in the counties provided the impetus for other celebrations of Arkansas’s folk culture. The Stone County Folk Festival began in 1941 as a result of work by county agents there to both provide entertainment and possibly inspire a draw for visitors to Mountain View and other areas of the central Ozarks. It certainly worked. The journal Recreation was sharing success around the country by federal agencies (this is at the end of the New Deal and program like Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to help communities develop and to provide cultural programming for the growing numbers of federal workers and servicemen joining the military. Although the early folk festival disbanded during World War II, Jimmie Driftwood and others used as a model for the Arkansas Folk Festival, which began in 1963 and became the state’s most recognized celebration of folk music. From the success of that festival, Driftwood, and the Rackensack Folklore Society he founded, helped establish the Ozark Folk Center in Mountain View.

The third connection between Cooperative Extension Services and folk music revival is a little more difficult to discern. But it is there in the form of the 1971 album Echoes from the Ozarks…. by “The Arkansaw Travellers.” It is one of a few published records included in the Leo Rainey Papers (MC1227). A graduate of the University of Arkansas and a rural development officer of the Cooperative Extension Services, Rainey helped organize the Arkansaw Traveller Folk Theatre at Hardy, Arkansas, in 1968 and was the Theatre’s Executive Director from 1983 until it’s closure in 1990. Scrapbooks, photographs, and promotional materials documenting the Folk Theatre are preserved alongside papers of Rainey’s rural development work, such as with the Ozark Foothills Handicraft Guild, and the organizational records of community development councils.

Through an academic thesis included in the Arkansas Collection, a rare World War II era publication, and a folk music album in a personal archival collection—three very different sources of information available in Special Collections—an historical picture of the folk revival movement in Arkansas begin to emerge.

Check back here for more discoveries from the Special Collections of the University of Arkansas Libraries on 365 McIlroy.

Joshua Youngblood is Research and Outreach Services Librarian for the Special Collections of the University of Arkansas Libraries. For more information about this blog post or for any questions about the Special Collections, contact him at jcyoungb@uark.edu, or 479.575.7251.