Labor was essential to the success of Robert E. Lee Wilson, who built a “Delta Empire” in Mississippi County, Arkansas. Starting in 1882 with 400 acres of swampland, by the time of his death in 1933 his holdings had grown to 65,000 acres of cotton planation and other enterprises.

To serve the needs of his workers, Wilson developed several small towns that provided all of the amenities his workers needed. Indeed, he took pride in providing the best housing and education available. In turn, the better conditions attracted more laborers to his businesses than similar enterprises. Still, working for Wilson also had a dark side.

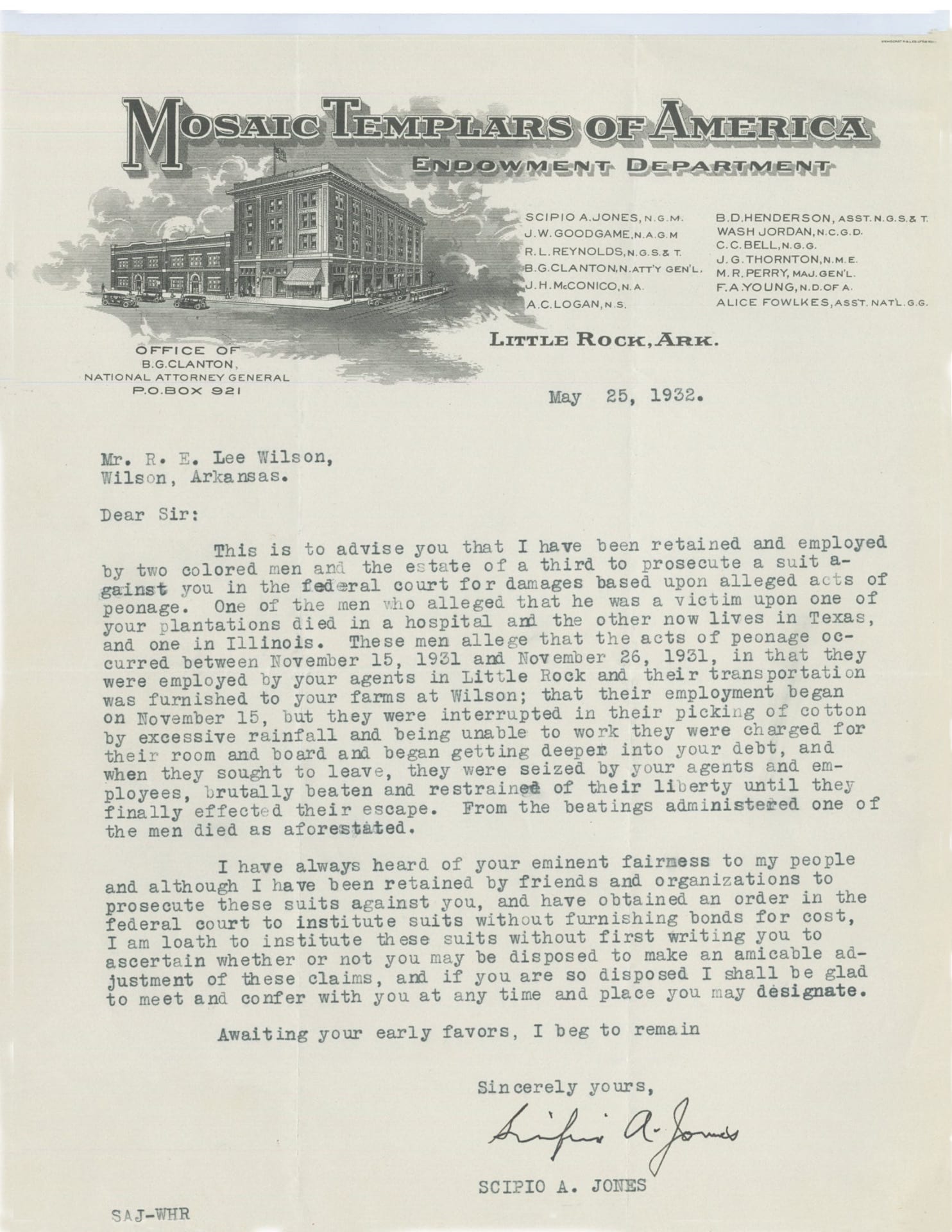

Wilson hired both white and black laborers. While many worked in his lumber business, stores and gins, most were employed as farmers. Arrangements were determined by the race of the employee. Whites worked as tenant farmers, paying rent, while African Americans were employed as sharecroppers, contracting for credit in return for a percentage of their crops. Both arrangements left farm laborers vulnerable, as the Wilson company employees could only receive goods from its stores. They commonly found themselves in debt, which the company refused to discharge. Accusations of peonage were made. For example, in one case in 1932, Wilson was pitted against African American attorney Scipio Jones.

Having represented twelve black men sentenced to death for their alleged roles in the Elaine Massacre before the U.S. Supreme Court, Jones informed Wilson that he represented three African American men who had been employed by his company the previous November. Severe rainfall had prevented the men from working. Nevertheless, they were charged for their room and board and amassed large debts. When they tried to leave, “they were seized” by Wilson’s men, “brutally beaten and restrained of their liberty until they finally effected their escape.” One man died from the beating, while the other two took refuge in Texas and Illinois. Wilson tersely replied to Jones, denying the accusations and inviting Jones to “take any steps that you see fit.” The outcome of the case remains unknown.

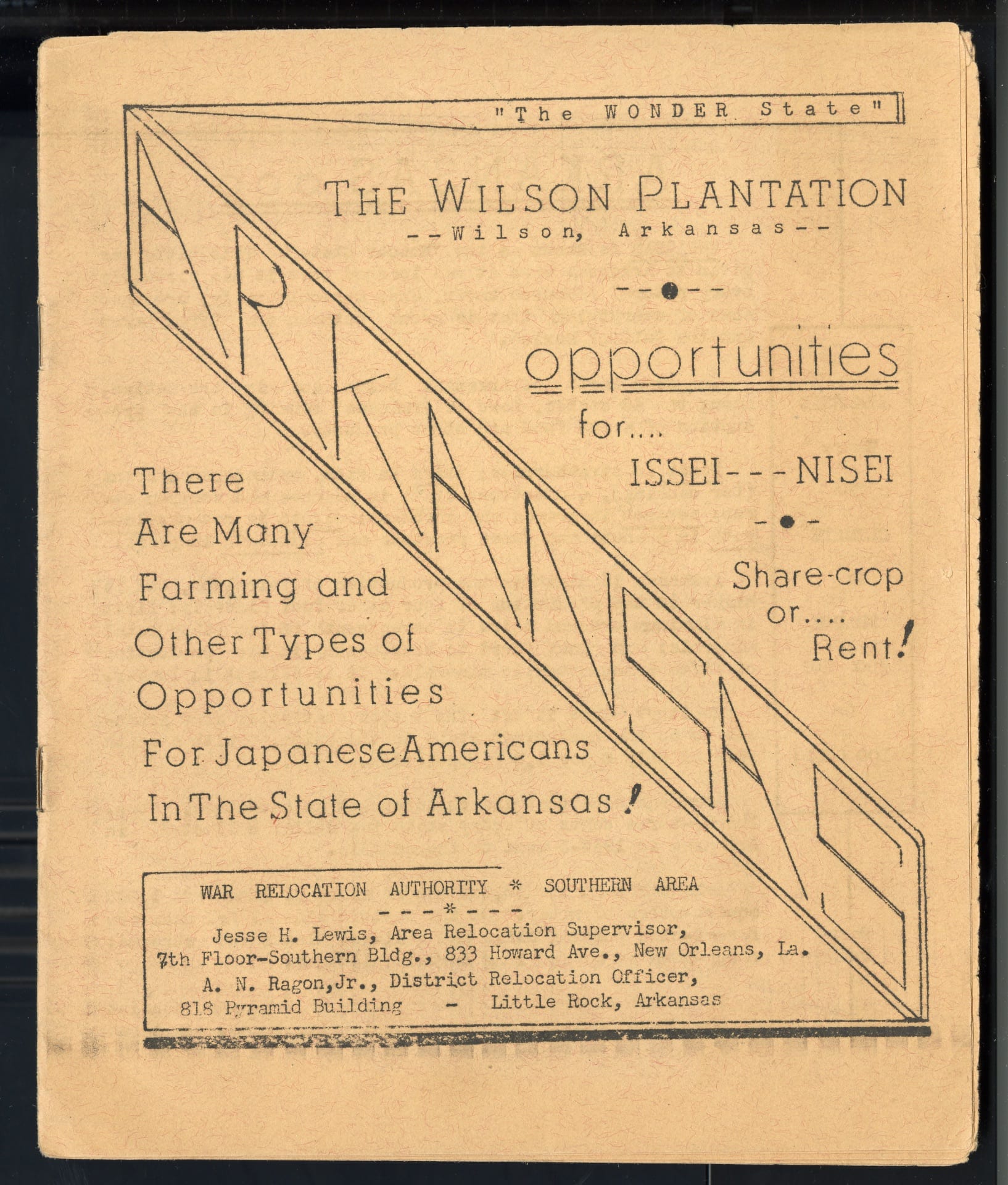

Bad working conditions exasperated by racist hostility caused black laborers to seek better alternatives. Spurred on by opportunities created by World War I and industries in northern cities, African Americans left the South in droves. The labor crisis continued throughout the 1930s. The decrease in black laborers forced southern planters to seek alternative sources of workers. In the 1940s, the Wilson company sought to use the labor of Japanese Americans held in Rowher internment camp in Desha County during World War II. Recruiting efforts began in 1943 and lasted until after the war, but yielded poor results. Instead, the company enlisted German prisoners of war, who left with the cease of hostilities in 1945. That same decade, another alternative presented itself—the federally-authorized use of Mexican laborers.

The Bracero (manual laborer) Program was created in 1942 under the auspices of the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement. The program allowed American agricultural enterprises to contract male Mexican laborers. The Wilson company employed thousands of braceros to assist during the harvest season (October-December), especially in the cotton fields. As early as 1925, the company had employed Mexican laborers. However, dubious practices resulted in the intervention of the Mexican Consulate, which investigated claims of peonage; an investigation by the Mexican Consulate yielded no tangible results. Reminiscent of the events of 1925, in 1948 the Lee Wilson and Company faced one of its worst crises. Almost 10% of the more than 2,800 braceros “deserted” Wilson plantations. Among the complaints was that the laborers had to deposit 10% of their wages into a company-managed savings account. Intervention by the Mexican Consulate resulted in the amount held back being reimbursed to numerous workers in 1949-1950. The Bracero Program was terminated in 1964.

Ultimately, the solution to the labor problem laid in modernizing production methods. By the 1950s, trends towards mechanizing farming and a decreased emphasis on cotton production greatly reduced plantation labor needs. As a result, the great armies of pickers that once crossed the cotton fields at harvest time disappeared.

For more information, see the R.E. Lee Wilson and Company Records (to be available to researchers in 2019).