[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.0.101″ background_layout=”light” text_line_height=”1.4em”]

This blog post is by Amanda White, a MA student in English at the University of Arkansas currently completing a rare books internship in the University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections.

The Special Collections Reading Room in Mullins Library is currently housing a new exhibit that features a variety of Bibles produced and owned during the 19th and 20th centuries. This exhibit examines American Bibles through the lens of what scholars call “history of the book” studies. This area of study is specifically concerned with a book as object. Rather than being interested in the contents of a book, the study of book materiality addresses a text’s material form, typography and formatting, methods of distribution, cost and use.

While the Bible represents a huge religious tradition that has been fundamental to the United States since its origins, this exhibit examines the American Bible as a complex, cultural artifact instead of a divine, sacred texts. By studying the Bible in terms of how it was produced, distributed, used, and regarded by both individuals and families, rather than specific denominations and religious organizations, researchers can understand this text’s unique place in American history, as well as its overall cultural significance and importance. The Bible is particularly well suited for this task for several reasons. Firstly, it was an extremely prevalent text, and highly valued, by Americans during this time. Secondly, it was used for a variety of purposes that went far beyond that religious. Lastly, it is an especially suited for this field of study, which still needs a great deal of attention from scholars. Specifically, during the 19th and 20th centuries, Americans were using the Bible in a variety of ways; and oftentimes, the physical makeup of a specific Bible dictated how it was used.

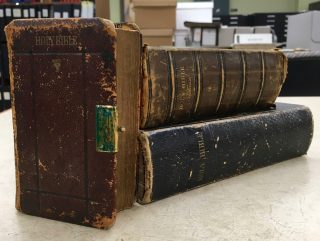

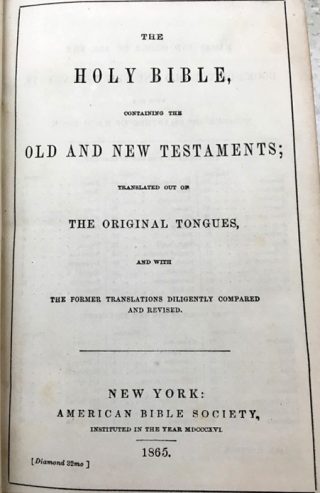

Book production and distribution in America had shaky beginnings and a long-winded transition period; even once various booksellers and printers had been established, the only books that were consistently being printed and distributed were books imported from England, reprints of books that were already popular, and religious texts like the Bible. In fact, the first Bible completed in America wasn’t produced until 1782; it really took until the 1800s for domestically produced Bibles to be cemented into American culture. The formation of the American Bible Society changed the Bible culture in America with its founding in 1816. Their earliest Bibles, like John H. Lupton’s, were very small, had little or no margins, hardly any appendixes or illustrations to speak of, and were bound in simple covers. Because this organization wanted to mass produce and distribute as many Bibles to as many Americans as possible, keeping it simple and inexpensive allowed them to meet this goal. Over the course of the 19th century, Bibles were becoming more elaborate and expensive in their production; and by the 1870s, little over half of the American population had these more extravagant Bibles. The Bibles housed in this exhibit not only represent the spectrum of Bibles being produced during this time, from the large to the small, and the cheap to expensive, they also demonstrate the various ways that individuals and families used Bibles during this time in America.

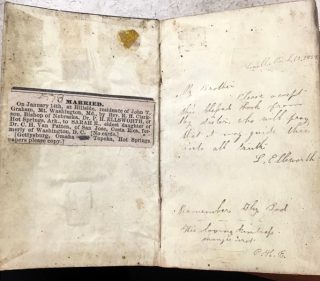

A common way Americans were using their Bibles during this time was as a way of recording various events, such as births, deaths, marriages, and even war-time services in their personal lives. In these instances, it’s very clear how a Bible’s materiality inclined it towards certain uses over others. Bibles being used for personal record keeping were typically small, portable, and inexpensive, especially when they were produced before the 1870s. Two examples of this text are the Ellsworth Bibles, owned by Sarah E. Van Patten and Prosper H. Ellsworth. Both these Bibles were produced and distributed during the 1850s. Sarah’s was given to her as a gift from her mother, which was very common with these smaller, personal Bibles. (The Bibles are now preserved as part of the Ellsworth Family Papers archives in Special Collections.)

Bibles kept for personal use often held notes with special meaning to the owner, such as favorite verses, sentiments from family members, and other items of importance. Sarah’s Bible contains all of these examples of marginalia; and of interest is a specific note written into the book of Ezekiel, captioned “Gettysburg…1865.” Accompanying this piece of marginalia is a page from Sarah’s personal notebook, which holds a pressed flower that is also captioned “Gettysburg 1865”.

In addition to containing many pieces of marginalia throughout the pages, there are several newspaper clippings sewn into the pages. Prosper’s Bible, while showing fewer signs of use and marginalia, also contains similar newspaper clippings. While it seems that Prosper was not diligent in reading the text itself, he still considered his Bible an appropriate place to record important events like marriages and deaths. These two small and seemingly insignificant texts hold a wealth of knowledge about the various ways individuals were using their personal Bibles during this time.

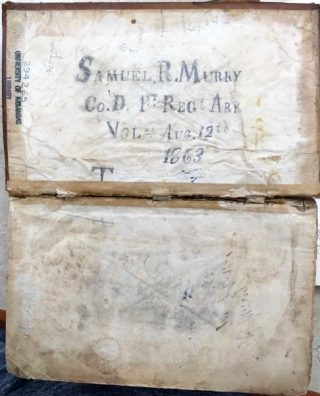

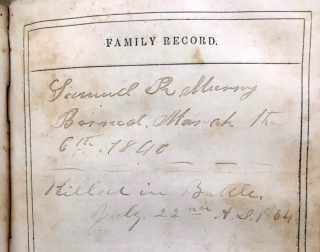

Another way Americans utilized their Bibles outside of strictly religious purposes was to record instances of war-time service. In some cases, the Bible was owned specifically by a soldier; in fact, there was an explicit push by states during the Civil War to get as many Bibles into the hands of their soldiers as possible. This extends to Samuel R. Murry and his Bible, also featured in the exhibit. Murry, a volunteer from the 1st Regiment Arkansas Infantry for the Union, served two years and carried this Bible with him. Like Sarah E. Van Patten, Murry used his Bible extensively, and marginalia can be found throughout its pages. Of particular interest are two longer notes. The first, written at the end of Revelation, appears to be Murry’s instructions regarding his loved ones in case he didn’t live to the war’s end. The second note is written on the “Family Records” page, by a completely different hand, and records Murry’s day of birth and the day he died in battle.

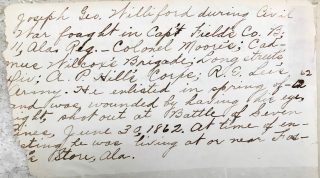

Much like Murry’s Bible, leaves from the Williford Family Bible also recount a family member’s war-time service. In addition to recording an extensive genealogy, this family took great care to record the Civil War experiences of a Joseph G. Williford, who served during 1862. (The Bible is included in the Williford Family Papers in Special Collections.) The Williford family clearly found the family Bible to be an appropriate place to record that Joseph Williford only survived the war because he discharged after losing his right eye in the Battle of Seven Pines.

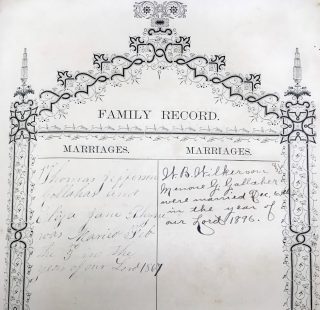

While these Bibles reveal unique insight about the individuals and families who owned them, and indeed demonstrate very popular ways of using a Bible during this time, the most iconic and prevalent by far was the use of a family Bible to record extensive genealogies. Unlike the individually owned Bible, these particular texts were typically much larger and elaborately decorated. To compete with the American Bible Society, and their near monopoly of small, inexpensive, personal Bibles, other booksellers began offering more detailed and expensive Bibles. The family Bible’s materiality indicates that not only were they intended to remain stationary, kept in one place, they were meant to be accessible to the entire family. These particular Bibles became more popular in the late 1800s, and often weighed up to 15 pounds; the Rhyne Family Bible is one such example. (The leaves are part of the Gallaher, Rhyne, Wilkerson Family Papers in Special Collections.)

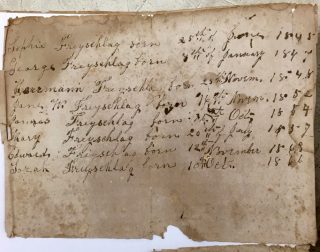

Another example of these larger family Bibles is the Hawkins-Walker Family Bible; and while there are only leaves from the actual text housed in the exhibit, they record a highly detailed and extensive genealogy. This particular genealogy records the descendants of the Freyschlag family, and lists more than 10 descendants between the years of 1844 and 1866. These meticulously genealogies, maintained by all members of the family, demonstrate another cultural use of the American Bible that extends not just beyond the religious, but the personal uses as well. (The Freyschlag family records are part of the Hawkins-Walker Family Papers in Special Collections.)

While individually- and family-owned Bibles were very useful and the most popular method of recording personal events such as births and marriages, another widespread use of the American Bible was for evidentiary purposes. During this time in American history, there was no standardized method of record keeping at either the national or state level, such as the birth certificate. In light of this, the American Bible became the primary way of proving your age that was accepted in civic and legal cases, because they were owned and maintained by entire families. American Bibles were consistently used to settle probate and statutory rape cases, as evidence for or against wrongful death claims, and to prove one’s age in exchange for a marriage certificate.

The reliance on family Bibles caused the states to push for a standardized method of record keeping in order to institute bureaucratic systems like healthcare reforms, sanitation, and compulsory vaccinations. This push to standardize was uneven across the country though; and especially in more rural states, like those in the South, the family Bible continued to be used for civic and legal disputes far into the 20th century.

The Bible and its cultural significance continues to intrigue Americans to this day. With the rising interest in genealogy, the Bible remains an important tool for tracing family origins. In addition to serving mainstream interests in genealogical studies, there is a real need for scholarly work where book materiality is concerned. Family Bibles, and the other rare books housed in Special Collections, are invaluable resources for students and researchers who wish to contribute work and in this area of study.

For more information on using the Bibles and family archives featured here, or accessing any of the invaluable resources on Arkansas and American history available in Special Collections, visit the department online, write to specoll@uark.edu, or call 479-575-8444.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]