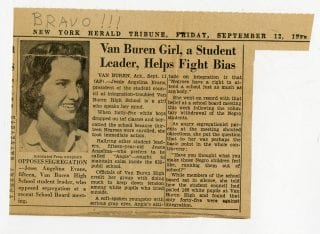

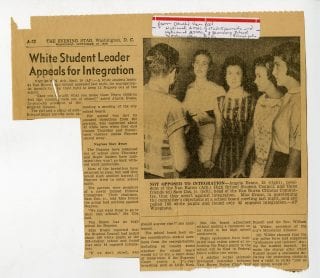

In September 1958, Jessie Angeline (Angie) Evans was a junior at Van Buren High School, and the school’s student council president. Her school had been peacefully integrated the year before, but that September, the integration crisis in Little Rock sparked new oppositions in Van Buren. An estimated 45 of her white schoolmates stayed home from school in protest of the integration of their own high school, and some students and townspeople protested outside. Effigies were burned; urgent messages were sent to the governor. However, Evans polled the student body and found the majority in favor integration. On September 9, Evans referenced that poll as she spoke out in favor of integration at a school board meeting, in the face of opposition from members from the Van Buren Citizens’ Council. Her stance was widely reported in the national and international media, including in Time and Life magazines. Mademoiselle magazine named her a woman of the year.

The University of Arkansas Special Collections has recently completed processing of the Jessie Angeline Evans Benham Papers (MC 2265), which includes fifteen boxes of correspondence from both supporters and critics, as well as newspaper clippings, publications, and other materials.

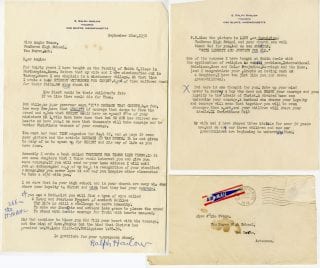

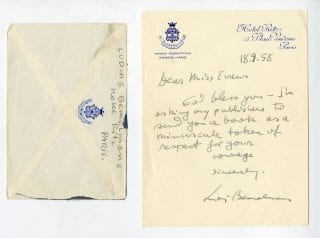

Evans’ correspondents include students, soldiers, school superintendents, ministers, children’s book authors, housewives, politicians, and civil rights activists. They wrote to her in words of encouragement, affirmation, denigration, and fearmongering. They wrote her singly and as couples, as Sunday School classes, Methodist Youth Fellowships, high school student councils, and women’s organizations.

They read about her in Life, in Time, in Mademoiselle; in the Toledo Blade (Toledo, OH), in El Comercio (Quito, Ecuador); in the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Daily Tribune, Oregon Journal, Los Angeles Harold & Express, Charlotte Observer, Arkansas Gazette, Detroit Times, New Haven Register, Denver Post, Boston Globe.

They warned of communist plots, violent rape, and the end of democracy in America. They praised her as Joan of Arc, a hope for the future, a bright girl like their daughter/granddaughter/niece. A number of correspondents felt the need to specify their own race, as they introduced themselves: “a middle aged colored woman” (Ruth Turner); “a white woman, married, the mother of one son” (Virginia Shield).

As letters poured in to Evans from across the globe, protests lessened in intensity, and students returned to school (without any direct assistance from Federal District Judge John E. Miller, who had declared the loss of civil rights for a few days to be of no great harm to anyone). Of the thirteen African-Americans enrolled at the beginning of the 1958 school year, however, only eight returned on September 22 to what the New York Times called “only minor taunts and hard looks” (“Van Buren Peaceful as Negroes Return to School,” New York Times 23 Sept. 1958 p1). They included Ernestine Norwood and her brother, Nathaniel A. Norwood, who was spat upon by his classmates but went on to serve in the U.S. Navy and earn honors in Vietnam; sisters Zelma and Palestine Roberts; and Freddie E. Bell, who had had a rock thrown at him. The lack of ongoing protests and strikes did not signal welcoming or inclusion for these students. Donald Jenkins Talley, writing decades later in the African-American newspaper Lincoln Echo, saluted his friend, George Huggins, “a black kid from Van Buren High School, class of 1959, who ate his lunch sitting on a rock all alone on Seniors Day” (“Integration at Van Buren High 1957.” Lincoln Echo September 1997, p5).

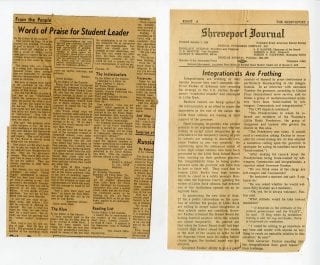

Newspaper clippings regarding Evans’ school board meeting comments (MC 2265, Box 15, Folder 63).

Newspaper clippings regarding Evans’ school board meeting comments (MC 2265, Box 15, Folder 63).